Writer: Arif Khan

Introduction

The Masdar Hossain Case (December 1999) is a judgment that redefined the constitutional and judicial landscape of Bangladesh. A common mistake regarding the Masdar Hossain case is the belief that it only settled the separation of the magistracy from the executive. This is wrong and misleading, as the judgment dealt with a far greater and deeper canvas of the state machinery itself, settling several grave issues once and for all, including the question of the Supreme Court's independence.

The case began as a simple matter of salary enhancement for judges who were aggrieved by an arbitrary and illegal reduction of their salaries. While it could have been a regular case if it only covered this issue, the judgment addressed the issues on a broader canvas and explored deeper layers of interpretation, allowing jurists from the bar and the bench to extract true hidden gems in the course of their arguments.

Int the beginning for the for the sake of clarity let me reiterate what did we achieve through this historic verdict?

What we achieved in Masdar Hossain Case?

The landmark Masdar Hossain case fundamentally re-asserted the principle of judicial independence in Bangladesh, transforming it from a mere constitutional ideal into a tangible reality. Through its directives, the judgment formally separated the judicial magistracy from the executive branch, ensuring that lower courts would operate under the superintendence and control of the Supreme Court, rather than being influenced by the executive. This pivotal ruling aimed to safeguard the impartiality and integrity of the judiciary by establishing a distinct judicial service and paving the way for an independent Bangladesh Judicial Service Commission, thereby strengthening the rule of law and enhancing public trust in the justice system.

Distinguished audience, I shall now elucidate the objectives that remained unfulfilled, notwithstanding the favourable judgement we received.

Despite the significant achievements of the Masdar Hossain judgment, several crucial aspects of true judicial independence in Bangladesh remain unfulfilled, indicating that the journey toward a fully autonomous judiciary is still ongoing!

One of the most persistent challenges is executive influence over judicial appointments, promotions, and transfers, especially at the higher judiciary level. While the lower judiciary's functional separation was largely achieved, the appointments of Supreme Court judges (both High Court and Appellate Divisions) can still be subject to political considerations, potentially compromising the judiciary's impartiality. The judgment called for an independent judicial commission to handle such matters, but its full mandate and implementation, free from political interference, are yet to be fully realized.

Furthermore, financial autonomy of the judiciary remains a point of concern. The judiciary's budget is often still controlled by the Ministry of Law, Justice, and Parliamentary Affairs, which can indirectly exert influence. True financial independence would mean the judiciary having greater control over its own budgetary allocations and expenditures, allowing it to manage its resources independently and efficiently.

Moreover, the "control" and "discipline" of the judicial service, as envisioned by the judgment, still face practical hurdles. While the Bangladesh Judicial Service Commission was formed, concerns about the ultimate authority and how disciplinary actions are handled without executive interference persist. There are reports of instances where judges face pressure or punitive measures for rulings that are not favorable to the executive.

Finally, the broader issue of a "judicial mindset" and the accountability of judges also comes into play. While structural independence is vital, it must be accompanied by a culture of judicial integrity, impartiality, and efficiency. Critics argue that even with formal separation, issues like corruption within the justice system, delays in trials, and instances where the judiciary might appear to succumb to political pressure continue to undermine public trust and the spirit of the Masdar Hossain verdict. The goal of a truly robust and independent judiciary, where every judge acts solely in accordance with the law and their conscience, irrespective of external pressures, is still a work in progress.

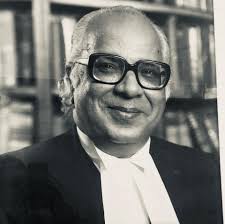

Before delving further into the judgment of the Masdar Hossain case, it is pertinent to consider another central figure of today's discussion: Barrister Syed Ishtiaq Ahmed.

Syed Ishtiaq Ahmed demonstrated a profound commitment to the rule of law, democracy, and constitutionalism, earning considerable public recognition for his unwavering advocacy of these principles and the independence of the judiciary. His dedication to these values was evident from an early stage; he endured imprisonment on two occasions during the Language Movement in 1952 and was incarcerated again in 1954 for his opposition to the imposition of Governor General's rule in the then East Pakistan. He was appointed Attorney General for Bangladesh in the mid-1970s, though his tenure was brief due to fundamental disagreements with the incumbent government. As a prominent and vocal opponent of the military and quasi-military rule of Hussain Muhammad Ershad throughout the 1980s, Syed Ishtiaq Ahmed was imprisoned in both 1983 and 1987 in consequence of his convictions and his pivotal role as a leading figure within the Bar, actively resisting the military-backed autocratic regime.

Recognised as a leading constitutionalist, he demonstrated his professional excellence in the famous 8th Amendment Case, where he led a relentless campaign against the amendment that had compromised the Supreme Court’s integrity, successfully getting it declared void in 1989. This was one of the monumental judgments in the history of Bangladesh. The 8th Amendment case was the first to shake the state and send a message that the CONSTITUTION IS THE SUPREME LAW OF THE LAND, and the Supreme Court has the exclusive responsibility to interpret it.

Throughout his life as lawyer, his arguments successfully defended the freedom of the press in various media suits. Following the restoration of the elected system in 1991, Syed Ishtiaq Ahmed played even more crucial role in transitioning to a parliamentary system and made pioneering contributions to the realisation of the non-party caretaker government. He was honoured with the 'Democracy Award' gold medal in 1995 for his contributions to the struggle for democracy, freedom of press, etc. Furthermore, during his time as an adviser to the Caretaker Government in 2001, he conducted the groundwork and laid the foundation to separate the judiciary from the executive.

While he did not engage in active politics, he held the position of Adviser or Minister on three occasions, accepting the role twice and declining once. He was a distinguished leader within the legal profession, instrumental in spearheading the movement for the restoration of democracy from military rule during the 1980s, an endeavour for which he was incarcerated on two separate occasions. Towards the end of his life, he became widely regarded as the nation's moral compass. His esteemed reputation as a meticulous lawyer, an individual of unblemished integrity, and a staunch advocate for democracy and the rule of law, coupled with his profound wisdom and extensive experience, rendered him a figure whose counsel was sought by all facets of the political spectrum, including politicians and various pressure groups. A keen observer of Bangladesh's political history would note the parallel evolution of the constitution's narrative and Ishtiaq's biography. This symbiotic relationship is evident in the trajectory of his legal career, wherein he participated in nearly all significant constitutional cases until his demise.

Syes Ishtiaq Ahmed , the visionary

Ishtiaq, the quintessential visionary, left an indelible mark on numerous domains. For the present discourse, our focus shall be exclusively directed towards his culminating struggle: the arduous pursuit of judicial independence. A pivotal question arises concerning the intrinsic originality of Ishtiaq's conceptualisation in this regard. For the preponderance of observers, judicial independence is frequently construed as a mere administrative triumph or, at best, a perfunctory victory secured by judicial functionaries over their executive counterparts. This interpretation, however, represents a profound and egregious underestimation of its true import.

For Ishtiaq, the imperative of independence transcended such simplistic notions; he posited it as a fundamental constitutional prerequisite. He perceived this relationship as intrinsically causative: for him, judicial independence was not merely a consequential outcome but rather a foundational antecedent. In contradistinction, prevailing perspectives frequently relegate the principle of separation of powers to the status of a resultant phenomenon.

We habitually articulate concerns regarding pervasive societal and political malfeasances, including, but not limited to, corruptions, arbitrary detention, instances of police brutality, the egregious phenomenon of enforced disappearances (colloquially termed "Goom"), extrajudicial killings, and the opaque operations of "Aynaghor." Yet, conspicuously, there persists a collective failure to apprehend the direct causal nexus between these egregious violations and the existence of a judiciary that is pale, reluctant, sidelined, subservient and tamed. Syed Ishtiaq Ahmed, however, possessed an unparalleled vision regarding the profound significance of this interrelationship. His diagnostic acuity concerning these systemic maladies was unimpeachable, and he proffered an ostensibly efficacious panacea. Nevertheless, I would contend that a momentous historical opportunity was irretrievably squandered by our collective recalcitrance to fully embrace his comprehensive perspective. Ishtiaq posited that a complete scheme for the functional and structural autonomy of the judiciary was inherently enshrined within the constitutional framework. Regrettably, this landmark judgment – undeniably of profound historical consequence – could only realise a partial fulfilment of this overarching vision, a limitation attributable to an overly circumspect hermeneutic approach to constitutional interpretation.

There is no doubt that this judgment transcends a mere legal declaration; it embodies a profound constitutional struggle. Within this struggle, it stands as "The Last Battle of Barrister Ishtiaq Ahmed," culminating in a "Radical Rethinking on Judicial Independence."

For decades following Bangladesh's independence, despite a clear constitutional mandate, the boundaries between the executive and the judiciary remained ambiguous. Judicial officers were regarded as integral to the broader civil service, thereby falling under executive purview concerning appointments, promotions, disciplinary actions, and even remuneration. This structural conflation fundamentally compromised the very notion of an independent judiciary – an indispensable pillar of any democratic state. It was a lingering colonial legacy that the written Constitution endeavoured to rectify; however, its implementation proved elusive for over two and a further quarter century (1972-1999).

Into this entrenched system stepped a courageous group of writ petitioners – district judges, additional district judges, and subordinate judges – who boldly challenged the status quo in 1994. Standing in solidarity with them, and lending their formidable legal acumen and unwavering resolve, were eminent legal figures such as Barrister M. Amir-ul-Islam, Dr. Kamal Hossain, and, indeed, Barrister Syed Ishtiaq Ahmed.

For Barrister Ishtiaq Ahmed, this particular case was more than a routine legal brief; it represented, in many respects, the culmination of a lifelong dedication to the rule of law and the sanctity of an independent judiciary. His arguments were not confined to technical interpretations; rather, they constituted a passionate articulation of fundamental constitutional principles. He recognised that genuine judicial independence was incompatible with executive dominance.

One of Barrister Ishtiaq Ahmed's most perceptive arguments, which proved to be a pivotal catalyst in this "radical rethinking," stemmed from his interpretation of the powers conferred by Article 116 of the Constitution. Whilst the Article stipulates that "The control (including the power of posting, promotion and grant of leave) and discipline of persons employed in the judicial service... shall vest in the President and shall be exercised by him in consultation with the Supreme Court," Barrister Ahmed cut through the formality. He boldly contended that the President's power here was merely formal. In reality, he argued, due to other constitutional provisions like Articles 48(3) and 55(2), the actual and real power of control rested with the Prime Minister – the chief political executive.

This constituted a revolutionary proposition. By exposing this executive reality, Barrister Ahmed amplified the critical importance of the subsequent clause: "in consultation with the Supreme Court." He forcefully asserted that if the executive, in the person of the Prime Minister, wielded the genuine power, then the consultation with the Supreme Court could not be a mere formality. It necessitated being endowed with substantial force. He insisted that this consultative process mandated the primacy of the Supreme Court's perspectives and opinions. Without this, he contended, Article 116 and indeed Article 116A (which proclaims judicial independence) would be rendered "mockingbirds" – constitutional provisions devoid of any substantive meaning. As the Prime Minister is the real wielder of power, this "consultation" must be given "teeth" to prevent Articles 116 and 116A from becoming "mockingbirds".

Furthermore, he logically connected this to Article 109, positing that the High Court Division's superintendence and control over subordinate courts necessarily extended to their presiding officers. This vision of judicial oversight, coupled with his challenge to executive power under Article 116, formed a cohesive argument for a judiciary truly independent in both function and structure. His brilliant articulation of the interconnectedness between these two articles (109 and 116), and his assertion that the Constitution contained a self-contained framework mandating an independent judiciary, which the Supreme Court ought to recognise, represents, in my view, his radical re-conceptualisation of this constitutional notion, a perspective uniquely envisioned by him. While the Masdar Hossain judgement was undoubtedly bold and pioneering in many respects, I contend that the Supreme Court ought to have embraced Syed Ishtiaq's singular and ingenious perspective: that no further constitutional amendments were requisite to achieve a complete functional and structural separation of the judiciary from the executive, thereby ensuring its independence. Nevertheless, this argument did not find favour with the Supreme Court. The Attorney General (Mr. Mahmudul Islam) opposed it, and even other counsel for the defendant was of the opinion that constitutional amendments were indispensable for the full realisation of judicial independence.

In Masdar Hossain, the judgment delivered by Chief Justice Mustafa Kamal evinced a conservative judicial approach, which could be characterised as the result of a ‘constitutional inertia’ (a tendency which prevents judges from interpreting the constitution creatively, which is clearly seen as a departure from established norms or precedent).

This ‘inertia’ was widespread during the pre-Anwar Hossain era and, to some extent, persisted into the post-Anwar Hossain period, as evidenced by cases such as Bangladesh Sangbadpatra Parishad (BSP) 43 DLR (AD) 126 and Kudrat-E-Elahi Panir 44 DLR (AD) 319. Despite the 1990s being a period of "Constitutional rejuvenation," marked by a consistent increase in progressive constitutional interpretation (e.g., Mujibur Rahman 44 DLR (AD) 111 and Dr Mohiuddin Farooque 49 DLR (AD) 1), indicating a departure from that inertia, the Appellate Division (AD) in this particular case did not fully embrace this evolving jurisprudential landscape.

Syed Ishtiaq Ahmed, alongside other prominent bar leaders, played a pivotal role in encouraging judges to broaden their constitutional understanding. His contribution in this case parallels that of Mr. Thurgood Marshall in Brown v. Board of Education, where Marshall endeavoured to persuade the American Supreme Court to identify and re-emphasise pre-existing constitutional principles rather than formulating novel remedies.

Why Last Battle

Syed Ishtiaq Ahmed tirelessly endeavoured to mould the nascent Bangladeshi judiciary, aligning it with the nation's constitutional framework. His remarkable efforts culminated in a masterful presentation to the judges. Despite his esteemed reputation as a distinguished jurist, an exceptionally successful lawyer, and a highly revered national figure, one of his most profound achievements lay in the judgment of the Masdar Hossain case. In this landmark ruling, he eloquently articulated his vision and embedded the very essence of judicial independence for the nation.

While not all of his arguments were ultimately accepted, this verdict nonetheless represented a milestone victory. Throughout his life, the principle of judicial independence remained central to his cherished values. The Masdar Hossain verdict was pronounced on December 2, 1999, and Syed Ishtiaq Ahmed passed away three and a half years later, on July 12, 2003.

Prior to his passing, he served as Law Adviser from July 15 to October 10, 2001. This role presented him with a historic opportunity to implement this momentous judgment. However, it is understood that the then-incumbent Prime Minister requested a temporary deferment of its final execution. The intention was for her government to oversee the implementation and thus be associated with this historic achievement. Syed Ishtiaq Ahmed honoured this commitment, but regrettably, the execution did not proceed as promised.

Astonishing assembly of legal minds

We must celebrate the achievement obtained in this great verdict for many reasons. Yet there one very exceptional one which make this case even special and extraordinary. The Masdar Hossain case is arguably the last case that brought together some of the last remaining finest legal minds in the history of Bangladesh’s judiciary. This case featured an extraordinary lineup of legal talent: Mr. Mahmudul Islam served as Attorney General, while Dr. Kamal Hossain, Syed Ishtiaq Ahmed, and Amir-ul-Islam appeared as counsel for the defendant. These four are widely considered among the greatest lawyers ever produced by this bar. Equally important were the judges presiding on the bench: Chief Justice Mustafa Kamal, and his other companion judges were Mr. Justice Latifur Rahman (later Chief Justice), Mr. Justice B.B. Roy Chowdhury, and Mr. Justice Mahmudul Amin Chowdhury (later Chief Justice). It was indeed an astonishing assembly of legal minds.

Among those involved, however, three names stand out due to their historical associations. Syed Ishtiaq Ahmed and Mustafa Kamal were close friends since their university days and were ardent supporters and activists of the 1952 Language Movement—a pivotal event that ultimately defined the nation's independence in 1971. Their friendship remained strong throughout their lives. They both studied in England, attending the London School of Economics, doing bar-at-law from Lincoln’s Inn and returned to Bangladesh around the same time which is early sixties. While they were popular cultural and political activists in university circles, and many expected them to enter politics, both chose the legal profession instead. Ishtiaq remained a lawyer for the rest of his life. Mustafa Kamal, though initially reluctant and having declined elevation twice, became a Supreme Court judge in 1979. Justice Mustafa Kamal authored several landmark judgments that caused a paradigm shift in Bangladesh's justice landscape, legal culture and judicial administration, while Syed Ishtiaq Ahmed continued his vigorous advocacy for the civil liberty, rule of law, democracy, freedom of press and constitutionalism.

In the early seventies, Mahmudul Islam began collaborating with Barrister Syed Ishtiaq Ahmed. This bond lasted until Ishtiaq’s death. Islam served as Ishtiaq's junior counsel for more than two decades; together, they fought several landmark cases involving critical constitutional issues. Many of these decisions are still consulted today as precedent. The jugalbandi (collaboration) of Ishtiaq and Islam, and their extraordinary contribution during the 1980s—ingeniously preserving the light of constitutionalism—deserves separate investigation. This collaboration culminated in the landmark Eighth Amendment case in 1989, which established the principle of constitutional supremacy for the first time in our history. Their jugalbandi continued until the mid-nineties.

Therefore, the Masdar Hossain case represented a full circle of life. In this case, we saw Syed Ishtiaq Ahmed as counsel, his most intimate friend, Mustafa Kamal, as Chief Justice, and Ishtiaq's most beloved junior, Mahmudul Islam, as the opponent (the Attorney General of Bangladesh). What a spectacular demonstration of legal intelligence and jurisprudential wisdom! In this light, the case can be viewed as a classic example of an epic battle between the mentor and his most brilliant disciple (Guru verus Shishya).

Post July Uprising and Independence of Judiciary

During the Awami League government's tenure (2009–2024), Bangladesh witnessed a colossal shift toward authoritarianism, largely facilitated by the systematic erosion of judicial independence. The government "weaponized" the judiciary to consolidate power and neutralize political opposition.

This was achieved through various means, including attempts to control judicial appointments and removals—notably via the controversial 16th Amendment—and the filing of thousands of politically motivated cases (Gaebi Mamla) against opposition leaders and activists. Allegations of coercion and the judiciary’s perceived failure to act as a check on repressive legislation, such as the Digital Security Act (DSA), contributed to a climate where the judiciary was no longer an independent arbiter of justice. This allowed the executive branch to suppress dissent and consolidate power unchecked.

Therefore, establishing an independent judiciary is crucial for achieving the transformational change needed to build a New Bangladesh. For meaningful reform to endure, we must heed the timeless wisdom of Barrister Syed Ishtiaq Ahmed.

The judiciary was vulnerable during the previous regime because its independence was never fully realized. This vulnerability stems from the unrealized implementation of the Masdar Hossain Case (actually not accepting the line of argument canvassed by Syed Ishtiaq Ahmad). Although a historic opportunity, the adopted approach created a conciliatory power arrangement between the executive and the judiciary, rather than fully implementing the constitutional mandate for independence.

Barrister Ishtiaq Ahmed, however, recognized the necessity of a complete and final separation to fulfill the constitutional scheme of judicial independence, arguing that no constitutional amendment was necessary for this separation. However, this bold proposition was not accepted by then Appellate Division.

A quarter-century has passed since that judgment (December 1999 – July 2025), during which Bangladesh has faced significant challenges to its culture of rule of law and democratic institutions. Following the July Uprising of 2024, the nation is now at a historic juncture/crossroad, facing a critical opportunity to reform various state organs. The central question remains: Will we finally rise to the occasion and implement the constitutional design for a robust, independent judiciary, thereby providing a firm foundation for rebuilding a New Bangladesh?

My heart say we must be able to do this because establishing an efficient and independent judiciary is not merely a technical requirement for governance; it is absolutely essential for realizing the core dreams and goals of the August 2024 student movement in Bangladesh.

The movement was fundamentally driven by a demand for justice, accountability, and the restoration of democracy, following a period characterized by extreme authoritarianism, fatal executive overreach, and widespread corruption. An independent judiciary serves as the cornerstone for achieving these goals, acting as a crucial check on power and ensuring the rule of law.

We know that the primary demand of the July movement was accountability for past actions, including the mass killing and violence used against protesters and the alleged human rights abuses and corruption under the previous administration. Therefore, we need:

- Checks and Balances: An independent judiciary is vital for maintaining a balance of power between the government’s three organs—the executive, the legislature, and the judiciary. If the judiciary is efficient and independent, it can prevent the executive from acting arbitrarily or consolidating excessive power.

- Prosecution of Abuses: Without an independent judiciary, those responsible for corruption, abuses of power, or violence against citizens cannot be effectively prosecuted. The judiciary must be free from political interference to ensure that cases, regardless of the defendant's political stature, are tried fairly and impartially.

Moreover, the 2024 July movement highlighted a strong desire for the protection of civil liberties, including freedom of expression and the right to peaceful assembly, which were often restricted under the previous regime. Therefore, we must ensure:

- True Guardianship of the Constitution: An independent judiciary is the guardian of the Constitution and the fundamental rights it guarantees. It has the power of judicial review to assess the constitutionality of laws and governmental actions, protecting individual liberties from state encroachment.

- Access to Justice: An efficient judiciary ensures timely and accessible justice for all citizens, particularly the most vulnerable. This includes addressing the backlog of cases and ensuring that legal processes are fair and not hampered by political or administrative delays.

The July movement strongly emphasized the need to dismantle corruption that had permeated various state institutions. Therefore, we must rebuild and redesign:

- Integrity of the Justice System: Judicial corruption undermines public trust and hinders the effective application of anti-corruption measures. An independent judiciary, free from corruption and external pressure, is essential for investigating and adjudicating corruption cases.

- Enforcement of Anti-Corruption Laws: When the judiciary is independent, it can enforce anti-corruption laws vigorously, providing a deterrent against illicit activities and ensuring that ill-gotten gains are recovered and perpetrators are held accountable.

Last but not least, the July movement led to the establishment of an interim government (IG) tasked with holding free and fair elections and reforming institutions. An independent judiciary is crucial for this transition phase too.

- Fair Elections: The judiciary plays a critical role in electoral disputes and ensuring the integrity of the voting process. An impartial judiciary guarantees that electoral processes are conducted according to the law and that the results accurately reflect the will of the people.

- Restoring Public Trust: The success of the interim government's reforms and the legitimacy of the upcoming elections depend heavily on public confidence in the judicial system. By demonstrating its independence and efficiency, the judiciary can help restore faith in democratic institutions.

In summary, an independent and efficient judiciary is the bedrock upon which the aspirations of the July 2024 movement—a Bangladesh rooted in justice, accountability, and democracy—can be built and sustained. Without it, reforms in other sectors are vulnerable to political manipulation and maneuvering, and the gains of the movement cannot be guaranteed.

Concluding Remarks

The Masdar Hossain case remains a pivotal moment in the constitutional history of Bangladesh, which can be characterized as Barrister Syed Ishtiaq Ahmed's "last battle". This judgment represents a "profound constitutional struggle", redefining the constitutional landscape regarding judicial independence. Ahmed’s arguments, rooted in a "radical rethinking" of the constitutional scheme, emphasized achieving functional independence within the existing framework. He uniquely contended that the phrase "consultation with the Supreme Court" used in Article 116 required "teeth" and the primacy of the Supreme Court's views, given that the real power rested with the Prime Minister.

The Masdar Hossain case is not just a chapter in our legal history; it is a living testament to the power of constitutional advocacy. It highlights how persistent and principled legal battles can reshape the very fabric of a nation's governance. Barrister Syed Ishtiaq Ahmed, in what could rightly be called his last great battle in this domain, contributed profoundly to this monumental shift. His arguments, rooted in a deep understanding of constitutional principles and the practicalities of governance, laid the groundwork for a judiciary that can truly stand as an independent pillar of the state.

This case, featuring an "astonishing assembly of legal minds" —including Syed Ishtiaq Ahmed, his close friend Chief Justice Mustafa Kamal, and his former brilliant junior Mahmudul Islam —provided a "definitive roadmap" and critical momentum for judicial independence. As a "living testament to the power of constitutional advocacy", the Masdar Hossain case demonstrates how principled legal battles can reshape a nation’s governance. We must honour this legacy by striving for a judiciary that is truly independent in spirit and function.

The journey towards full judicial independence is continuous, but the Masdar Hossain case, fueled by the radical thinking of lawyers like Barrister Ishtiaq Ahmed, provided the definitive roadmap and the critical momentum. Let us remember this legacy and continue to strive for a judiciary that is not just independent on paper, but truly independent in spirit, in function, and in the eyes of every citizen.